PRIDE or FALl

Revolutionary Pride and a Lasting Legacy By Eric Lambkins II Tommie Smith and John Carlos know the paradoxical and quizzical struggle of pride

Revolutionary Pride and a Lasting Legacy

By Eric Lambkins II

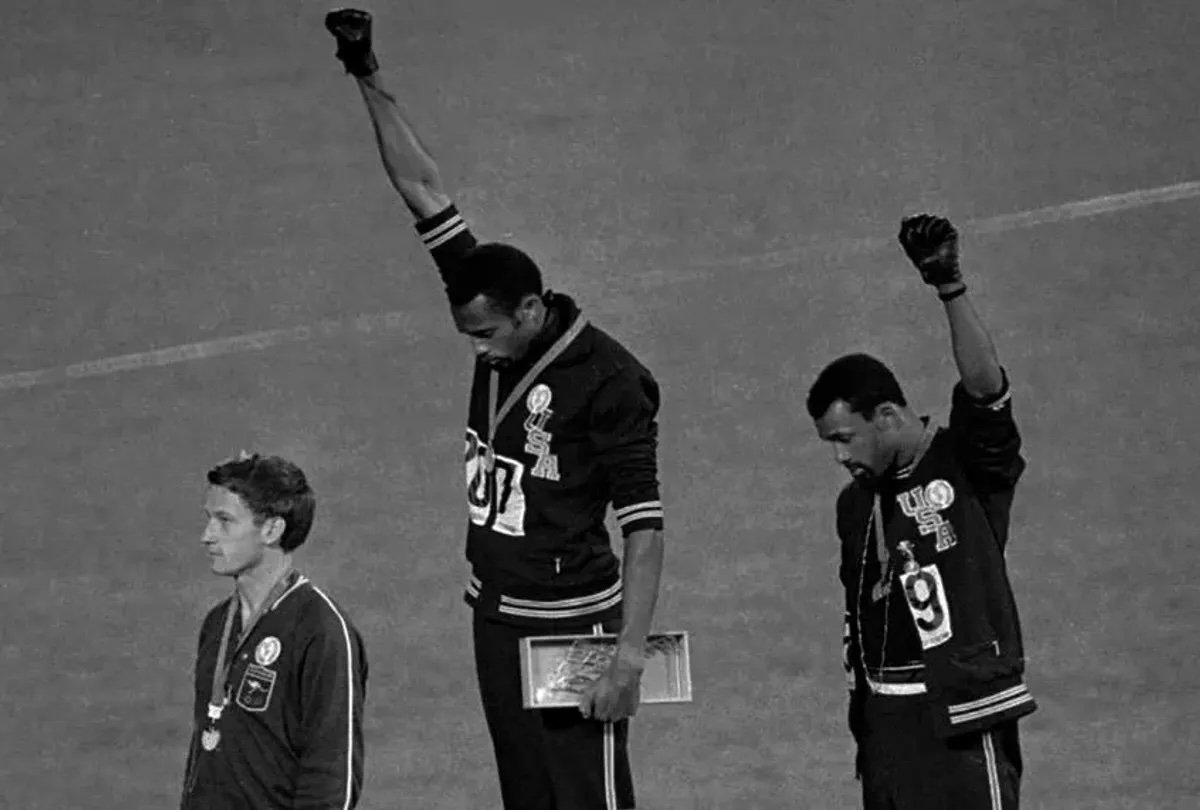

Tommie Smith and John Carlos know the paradoxical and quizzical struggle of pride. It’s a double-edged sword that catalyzes athletes’ ambitions—to push the limits of their minds and bodies to unfathomable ends to achieve greatness. Conversely, it can also yield decisions that convolute and obscure careers and sometimes lives, with occasionally irreversible decisions. Athletes whose pride defined their careers are Tommy Smith and John Carlos, the black Olympic sprinters whose Black Power salute during the medal presentation at the 1968 Mexico Olympics galvanized a global conversation about racial inequality and injustice and made the two Americans revolutionary icons.

Smith and Carlos stood atop the podium, fists adorned in black gloves, raised to the heavens and made a statement that reverberated globally. Their protest was not confined to the Olympic Stadium and village; it reached the far reaches of alleyways, street corners, suburbs, and mansions worldwide. They were more than mere athletes; they instantaneously became representations and mouthpieces for Black Americans and symbols of resistance, using their platform to advocate for the plight of Black Americans and oppressed people.

In that moment, pride wasn’t just personal; it became political. Smith and Carlos’ protest proved costly, leading to their expulsion from the Olympic Games and a lifetime of scrutiny and struggle. Yet, in their hearts, they understood that their gold medals paled compared to their struggle for justice, equality, respect, and self-determination.

“When I came back to California, people shunned me like I was hot lava,” Smith said. “I had a young son and a wife, and I had to work, but the only jobs I could find were, like, washing cars. Had I been a white guy who held 11 world records, I believe no matter what I would have done in Mexico City or in the Olympic Games, I would have had some backing.”

Reflecting on that memorable moment, Carlos said that Smith’s glove on his right hand signified “the power within Black America,” while Carlos’ stood for “Black unity.” Smith’s black scarf adorned around his neck stood for Black pride, and the black socks without shoes symbolized “Black poverty in racist America.” Carlos’ bead necklace represented the lynchings of Black Americans. The weight of that pride and profound sense of responsibility—compelled the two medalists to act. It’s a burden many Black athletes carry: the knowledge that their voices can serve as a mouthpiece for their communities, even as they navigate the complexities of their futures.

This balance for Black athletes between self-advocacy and community representation isn’t new. The legendary boxer Muhammad Ali faced a similar quandary when he refused to fight in Vietnam, citing his opposition to the war and its disproportionate impact on Black Americans. Ali’s backlash was instant and staunch, causing the heavyweight champ to lose his title, be stripped of his boxing license, and be imprisoned. Nonetheless, he stood firm, displaying that pride requires that even in the face of adversity, one must stand resolved for one’s beliefs. He famously said, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want.”

Then there’s Colin Kaepernick, who took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality and systemic racism. Kaepernick’s pride and protest immensely cost him, like Smith and Carlos, and he came under fire. The former San Francisco 49er quarterback became a league-wide pariah after he opted to kneel during the national anthem to protest police brutality and racial inequality, losing his job and facing a firestorm of criticism. Despite the abuse he’s faced, Kaepernick has remained steadfast in striving for equality with a sense of pride that has transcended his on-field play and typified his life’s purpose. The former quarterback has grasped the gravity of how his actions inspired a movement and has unflinchingly remained a staunch advocate for social justice.

A painful truth is elucidated by the sacrifices made by these athletic icons: using one’s platform to speak truth to power often comes at a severe personal cost. For Smith and Carlos, their Olympic protest led to struggles in their professional careers. Kaepernick was blackballed from the NFL and has not played another snap. Numerous athletes abandoned them, and what might have blossomed from the sponsorship opportunities from their feats withered under the hurdle of social contention. Nonetheless, their de facto social embargo has since seen the three embraced as trailblazers and iconoclasts, with their actions now revered with deserved reverence.

Consequently, pride can therefore be perceived as more than an unfavorable trait. It can compel athletes to challenge the status quo, push for change, and give credence to marginalized voices. However, it also requires vulnerability and sacrifice, which not everyone is prepared to embrace. The reality is that pride can cost individuals endorsements, team appointments, and favor from the public. Yet, for many, their legacy—courage, integrity, and solidarity—withstands time, and they write their names in the annals of history and our collective consciousness.

In thinking about the sacrifices of numerous Black athletes, we must acknowledge how vital of a role and salient their pride is. Their pride is a reminder that in the ongoing struggle for justice, the path to equality is often riddled with pain and requires sacrifice. Their stories are epochs of prideful resilience, reminding us all that while the stakes remain lofty, their voices can resonate far beyond the boundaries of the game’s lines and foster conversations that challenge and inspire future generations.

Their journeys encourage a new understanding of pride: it has immense potential for good, can unite communities, and inspire change, even when it demands significant personal sacrifice. That may be the most lasting legacy an athlete can establish.

When You Have too Much Pride, Your Career Can Die

By Mykell Mathieu

But yo, y’all ain’t hearin’ me!”

My homie facin’ life, he told me that my pride is my biggest enemy” rapper Schoolboy Q said in his song “Black THougHts” from his critically acclaimed Blank Face LP.

This quote has been a true statement for a long time. Pride can be someone’s biggest enemy, especially when it comes to athletes. One athlete who comes to mind is former Ohio State star Maurice Clarett.

Coming out of high school, Clarett was ranked among the top 100 players in the country. The Ohio native was a 2002 U.S. Army All-American and received several college offers. He chose Ohio State in February 2002, where he truly made a name for himself on the gridiron.

Clarett dominated his freshman year with the Buckeyes, rushing for 1,237 yards (then a school record for a freshman) and scoring 18 touchdowns, which helped the Buckeyes to a 14–0 record. Ohio State’s undefeated record led the team to the 2002 BCS National Championship game, where they matched up with the defending champion, the Miami Hurricanes.

The freshman back had big moments throughout the game. After an interception by then-Ohio State quarterback Craig Krenzel, Clarett stripped the ball from the Miami defender to return it to the Buckeyes, which they turned into points, leading to a 10-point lead. Clarett made “the play” of the game when he scored the game-winning touchdown on a 5-yard run in the second overtime. Clarett was a 19-year-old football star on top of the world. Then pride got in the way, and everything went downhill.

Incidents on and off the field marred the rest of his stay at Ohio State. Some would say he thought he was bigger than college football and Ohio State. This led to his dismissal from the university and his move to Los Angeles.

While in Los Angeles, Clarett challenged the NFL’s rule that a player must wait three years after graduating from high school to declare for the draft. Clarett was barred from the 2004 NFL Draft and couldn’t return to play in college due to signing with an agent.

After sitting for a year, Clarett entered the 2005 NFL Draft and was the Denver Broncos’ final pick of the third round (#101 overall). After sitting for nearly two years, Clarett was never the same player. With poor play on the field and more incidents, his NFL career was quickly over.

The former Ohio State continued to spiral after his failed NFL career. Trouble with the law led to multiple arrests, and his life looked much different from what he expected after the 2002 National Championship. When ego and pride get in the way of greatness, it is terrible to see. Humbling yourself is key to continued success as an athlete, and that’s what we didn’t see from Clarett.

He has since turned his life around after his mistakes off the field, but I bet he would tell you that too much pride leaves you in a big mess.

Tua Tagovailoa’s Relentless Drive: Is His Pride Pushing Him Toward a Medical Tragedy?

By Jackie Rae

My colleagues raise excellent points. Pride can be a powerful motivator for athletes, driving them to stay focused on their goals and push toward success. However, it can also be a double-edged sword, causing them to believe their own hype and, in doing so, potentially derailing their career. And while a ruined career may seem like the worst outcome, the true cost of unchecked pride can be far greater. It can damage relationships, erode mental well-being, or even worse, cause irreparable damage to their body.

When the Miami Dolphins drafted Tua Tagovailoa with the 5th overall pick in the 2020 NFL Draft, they hoped to find their franchise quarterback, a player with the potential to lead the team into a new era of success. Tua has remarkable talent, but his injury history raises the question: Will his pride and determination to play eventually lead to a life-threatening injury?

While he is known for his paralyzing NFL injuries, Tua’s injuries date back to his college career with Alabama. Perhaps the most well-known and significant injury of Tua’s college career came in November 2019 during a game against Mississippi State. Tua dislocated his right hip and suffered a posterior wall fracture after being hit while rolling out of the pocket. The injury was eerily similar to the one that ended Bo Jackson’s career and required immediate surgery.

After being drafted by the Dolphins, Tua’s health remained a point of emphasis. He began his rookie season as a backup to Ryan Fitzpatrick, partly to ease him back after the hip injury. When Tua took over as the starter midway through the season, he played solidly but was briefly benched in a few games, which some speculated might have been due to lingering health concerns. Though he made it through his rookie season without significant injuries, there were still whispers about his long-term ability to stay on the field.

More injury woes marred Tua’s second NFL season. Early in the 2021 season, he suffered fractured ribs in a Week 2 game against the Buffalo Bills, sidelining him for several weeks. Later in the season, he also dealt with a fractured middle finger on his throwing hand, which caused him to miss another game. While fans and coaches may have viewed these injuries as typical, they highlighted Tua’s inability to stay healthy. And perhaps even foreshadowed the heartstopping injuries that were yet to come.

The most alarming chapter of Tua’s injury history came during the 2022 season when concussion issues took center stage. In Week 3, during a game against the Buffalo Bills, Tua appeared to suffer a head injury, stumbling to the ground after taking a hit. Despite visible signs of a potential concussion, he returned to the game, and the Dolphins later declared it a back injury.

Just four days later, on Thursday Night Football against the Cincinnati Bengals, Tua suffered a horrifying head injury when he was sacked, slamming his head onto the turf. He lay motionless on the field, his fingers seizing up in a fencing response—an involuntary reaction associated with brain trauma. He was carted off and taken to a hospital, sparking a massive debate about the NFL’s handling of concussions.

Tua missed multiple games after the incident but eventually returned. However, the severity of these concussions has raised concerns about his long-term health and the potential risks he faces if he continues to suffer head injuries.

Then, in early September, Tua was sidelined with yet another concussion in the third quarter of the Dolphins’ 31-10 loss to the Buffalo Bills. After scrambling up the middle for a first down, he lowered his shoulder to initiate contact with Bills safety Damar Hamlin. After his helmet collided with Hamlin’s body, Tua collapsed and exhibited a fencing response, where a person’s arms move into an unnatural position as a result of brain trauma.

Dolphins medical staff rushed to his aid, tending to him for several minutes as players gathered around. Despite the scare, Tagovailoa eventually walked off the field and into the locker room on his own. Currently, the Dolphins and those close to Tua say he is still planning to return.

Love for the game is a beautiful thing. Faith in your ability to play at a high level is awe-inspiring. But, having so much pride that you fail to read the writing on the wall and listen to what your body is saying is cause for concern. Whether it is pride, love for the game, money, or all the above, Tua Tagovailoa is currently on the road to a medical tragedy. One can only hope he will make a U-turn before his family, friends, and fans have to bear witness to a crisis that could have been avoided.